John Lennon asked us to ‘imagine there’s no countries’—easy enough when West were the beneficiaries of such a thought experiment. But are we truly prepared to relinquish our role as apex predators in the system, or are we quietly turning back to mercantilism to preserve our status?

The debate over trade and national power is at the forefront of global politics, with two dominant frameworks—mercantilism and globalization—shaping policy in consequential ways. In today’s polarized climate, the debate is especially relevant—on one side, the right views globalism as a path to a WEF-controlled future, complete with 'eating bugs' and erasing national sovereignty; on the other, the left sees mercantilism as a relic of racist, imperialistic policies that stifle equality and opportunity. Neither model is morally superior. Both have winners and losers. This comparison is not about declaring one side 'correct' but rather understanding the trade-offs each model presents, especially in the context of today’s ideological divide.

The Long Road to Global Trade

Globalization didn’t suddenly appear with smartphones and shipping containers—it’s been unfolding for over two thousand years.

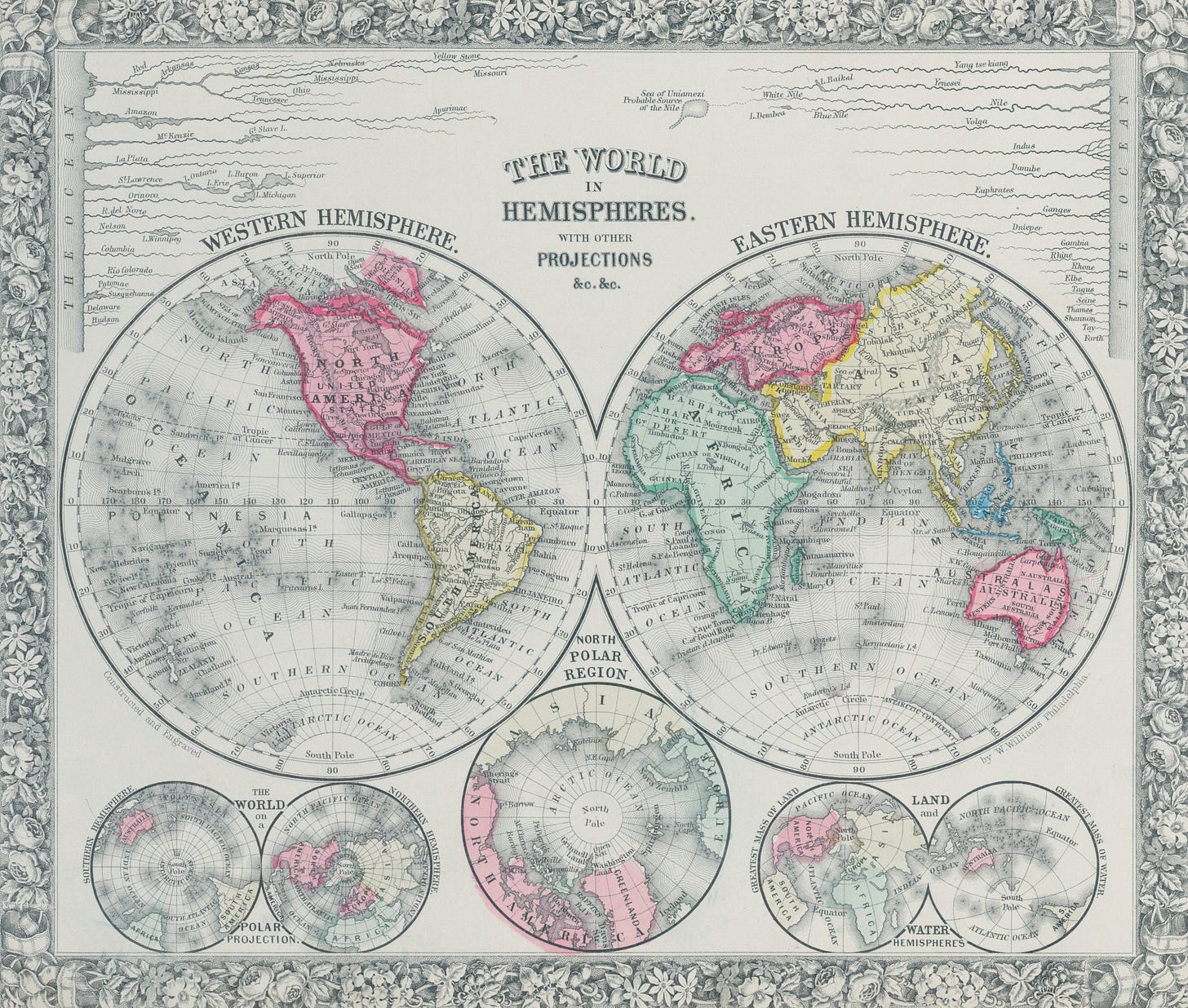

It began with caravans and galleys: the Silk Road (circa 130 BCE) and Roman trade routes stitched early connections between East and West. Goods moved, ideas followed, and empires got rich.

The colonial era (1500s–1800s) expanded the map—and the imbalance. European powers built vast trade networks, often fueled by conquest, coercion, and a brisk trade in sugar, spices, cotton, and human lives.

Then came the Industrial Revolution. Steamships, railroads, and mechanized factories turned local economies into global machines. Raw materials poured out of colonies; finished goods came roaring back from Europe’s smoke-stacked cities.

After World War II, the world tried to keep the peace with Bretton Woods institutions like the IMF and World Bank, later joined by the WTO in 1995. Free trade became the favored prescription, with the United States playing lead economist.

By the 1990s, the Cold War had thawed, China had opened for business, and the internet connected nearly everything. Global supply chains sprawled. “Made in China” became shorthand for modern manufacturing. And somewhere in the background, the World Economic Forum picked up a lot more name recognition.

The Benefits of Trade Globalization

Lower Prices & Consumer Choice

Goods made in lower-cost regions become accessible globally. A consumer in Canada can buy electronics made in Taiwan, avocados from Mexico, and clothes from Bangladesh.Efficiency through Specialization

Countries specialize in what they do best (comparative advantage), boosting productivity. Germany focuses on precision machinery; Brazil exports soybeans and coffee.Larger Markets for Producers

A startup in India or a factory in Vietnam can now sell to customers in Europe or North America, bypassing local limitations.Innovation & Knowledge Transfer

Exposure to global competition encourages innovation. Technologies spread faster, raising the tide for all.Job Creation in Developing Countries

For many nations, manufacturing jobs have lifted millions out of poverty—particularly in Asia.

The Downsides (and Who Pays the Price) of Globalism

Deindustrialization in Rich Countries

Western nations, especially the U.S., Canada and parts of Europe, saw factories close and jobs move abroad. The "Rust Belt" is a byproduct of this shift.Labor & Environmental Exploitation

Companies often outsource to nations with cheaper labor and weaker regulations, leading to sweatshops and environmental degradation.Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

The COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical tensions (like U.S.–China trade wars) revealed how fragile global supply chains can be.Unequal Gains

While multinational corporations and skilled workers often benefit, many working-class communities are left behind.Cultural Erosion & Loss of Sovereignty

As global brands expand, local traditions and businesses fade. Nations also lose control over key industries or technologies.

We’ve been on a linear globalist path for some time, but—contrary to my childhood worldview—history isn’t written in a straight line, always trending up and to the right. Cracks are starting to form and those who’ve paid the price are now demanding change. This creates an opening for another framework to find its place in the ideological purview.

Mercantilism: The Original Trade War Strategy

Before globalization, there was mercantilism—a dominant economic theory where the goal wasn’t cooperation or efficiency, but national power, stockpiled gold, and protectionism. From 16th-century empires to 21st-century trade tariffs, the logic of mercantilism echoes in today’s geopolitical tensions.

Mercantilism flourished between the 1500s and 1700s, especially in Europe. Powers like Spain, France, Britain, and the Dutch Republic used mercantilist policies to bankroll their empires and militaries. The goal was simple: export more than you import, hoard precious metals, and treat trade like a zero-sum game to protect domestic interests.

Colonies weren’t just scenic holdings—they were economic assets. They shipped raw materials home at bargain prices and bought back finished goods at a premium, whether they liked it or not.

At the heart of mercantilist thinking is the belief that exports generate national wealth, while imports represent a drain on the economy. To maintain a favorable balance of trade, governments must intervene aggressively—through tariffs, trade monopolies, colonial expansion, and strict import restrictions. These tools weren’t just economic policy; they were instruments of power, used to protect domestic industries and project national strength. Sound familiar?

Mercantilism is, at its heart, economic nationalism—with the ultimate goal of strengthening the state.

The Power of Mercantilism

Strengthened the State

Mercantilism helped central governments consolidate power, fund armies, and build navies during the age of empire.Built Domestic Industry

High tariffs and subsidies nurtured early manufacturing sectors, laying industrial foundations.Encouraged Self-Sufficiency

Countries relied less on foreign powers, aiming for control over critical resources and production.Stimulated Exploration and Expansion

The quest for gold and trade routes led to global navigation, colonization, and the spread of new technologies.

The Drawbacks of Mercantilism

Zero-Sum Thinking

Treating trade as a competition ignored the potential for mutual benefit and innovation through cooperation.Colonial Exploitation

Mercantilism often justified brutal extraction of wealth from colonies, enriching European powers at others’ expense.Inefficiency and Corruption

Government-controlled monopolies stifled competition and innovation. Many mercantilist regimes were riddled with cronyism.Trade Wars and Conflict

Mercantilist policies frequently triggered naval wars, embargoes, and retaliation, creating geopolitical instability and tension.Stagnation Over Time

Overprotective systems discouraged entrepreneurship and dynamism in the long run.

Mercantilism Today: Is It Back, Is It Wrong?

While few governments openly identify as mercantilist, the playbook is quietly being dusted off. China’s state-directed capitalism relies heavily on export-led growth and tight control over strategic resources. In the EU and U.S. (most notably), a tidal wave of tariffs, reshoring initiatives, and industrial subsidies reflect a shift toward protecting domestic production. Across the globe, national security concerns are driving countries to tighten borders and secure supply chains in critical sectors like rare earth elements, energy, and semiconductors. These policies reflect a shift from globalist efficiency to nationalist resilience—a sign that, in times of uncertainty, mercantilism’s allure returns.

Mercantilism is a reminder that trade is never just economic—it’s strategic. Whether used to build empires or secure semiconductors, it prioritizes power over price, and sovereignty over synergy.

The big question isn’t whether mercantilism is “right” or “wrong.” It’s: how much national control are we willing to trade for economic efficiency—and vice versa?

Mercantilism is built on a zero-sum worldview. It assumes one nation’s economic gain comes at another’s expense. The mercantilist goal is not cooperation, but national strength: self-sufficiency, surplus exports, and a hoard of hard currency. Picture a paranoid empire stacking gold behind thick castle walls.

Globalization, by contrast, treats trade as a mutual opportunity. It’s based on the idea that when nations specialize and exchange, everyone benefits. The goal is efficiency, innovation, and interconnected prosperity. Imagine a spreadsheet optimizing global labor, production, and consumption across invisible borders.

Mercantilism deploys a muscular toolkit: tariffs, quotas, trade monopolies, government subsidies, and colonial extraction. It demands strong borders and stronger navies. Globalization’s tools are more technocratic: free trade agreements, liberalized currency regimes, intellectual property protections, and seamless cross-border outsourcing. Where mercantilism enforces order through force, globalization prefers agreements and arbitration.

Each model has its virtues. Mercantilism can foster domestic industry, build resilience, and limit strategic vulnerabilities. It rewards patience and long-term national planning. Globalization, meanwhile, expands consumer choice, reduces prices, and accelerates technological progress by connecting the smartest ideas with the cheapest labor and the biggest markets.

But each has deep flaws. Mercantilism often leads to inefficiency and stagnation, fostering cronyism and monopolies. Its pursuit of national gain at the expense of others frequently spills into conflict. Globalization, while efficient, can be dangerously brittle. It leaves supply chains exposed to disruption, allows corporations to pit nations against each other in a race to the bottom, and concentrates power and profit in the hands of a global elite. For all its promises, globalization has produced stark inequality, cultural homogenization, and the slow erosion of industrial jobs in many developed economies.

In mercantilist systems, domestic producers, central governments, and military contractors typically benefit. Consumers, on the other hand, pay higher prices, and innovation may stagnate under protectionist shields. Under globalization, multinational corporations, urban consumers, and nations with comparative advantages flourish. The losers include working-class labor in developed nations, regions dependent on outdated industries, and anyone vulnerable to supply bottlenecks or price shocks.

The Ideological Divide: Left vs. Right, Globalist vs. Nationalist

In contemporary politics, globalization is frequently associated with left-leaning or progressive ideologies. These groups tend to emphasize international cooperation, humanitarian values, open borders, and the belief in mutual economic benefit. Globalist policies often align with environmentalism, liberal democracy, and the idea that interdependence reduces the chance of conflict.

Mercantilist thinking, on the other hand, has found a renewed home on the political right. Nationalist conservatives and economic populists emphasize sovereignty, protection of domestic labor, and strategic autonomy. They view globalization as a threat to local culture, national security, and economic self-determination. Trade is seen not as a shared venture but as a competitive battlefield.

This division has become increasingly polarized, with globalization framed as either utopian idealism or corporate betrayal, and mercantilism portrayed as either patriotic resilience or dangerous regression. The problem isn’t in the policies themselves, but in the absolutism with which they’re adopted. In reducing economic strategy to political identity, nuance is lost—and with it, pragmatic problem-solving.

But here's the irony: neither the political left nor the political right fits neatly into the frameworks they now champion. The left, which traditionally defended labor and manufacturing, now supports global systems that have hollowed out industrial jobs. The right, which once celebrated free-market capitalism, now favors tariffs, subsidies, and state intervention to protect domestic industry. Both sides have adopted positions that contradict their historical philosophies—evidence that the ideological divide is more tribal than rational.

Neither side has a monopoly on truth. Globalism isn’t inherently virtuous; it’s vulnerable to exploitation. Mercantilism isn’t inherently xenophobic; it’s a strategy with historical roots in survival and strength. Yet, in today’s discourse, choosing one often means rejecting the other wholesale. That’s a mistake.

Looking forward

Reality resists binaries. Nations need to be globally connected and domestically resilient. The smarter conversation isn’t about which model to worship, but how to combine their strengths without falling into ideological traps-–hoping we can reap benefits without paying the full price. In geopolitics, as in economics, every advantage carries a cost—and no ideology escapes the fine print.

As politicians continue to sell one-way tickets in either direction, we should step back and consider the full picture. And after doing so, we should pressure them to pursue more nuanced, forward-thinking policies—for all our sakes.

<3

Derek

YES! They are losing and the World is changing to Populism.